William Sidney Mount

William Sidney Mount (26 Nov 1807 to 19 Nov 1868), “the originator of American genre painting” was a descendent of Timothy Mills of Mills Pond. The Long Island Museum of American Art, History, & Carriages owns many of William Mount’s works and the text of this section is taken from the Museum’s past exhibitions, reproduced here with permission.

“A Long Island native, Mount (1807-1868) is widely credited as the originator of American genre painting.”

“Before William Sidney Mount, few American artists had looked to the lives of ordinary folk for inspiration, for only figures out of history, myth, literature, or the Bible were considered worthy of representation. Mount’s works depicting country people were enormously popular, and laid the foundation for a school of American genre painting whose effects are still felt.”

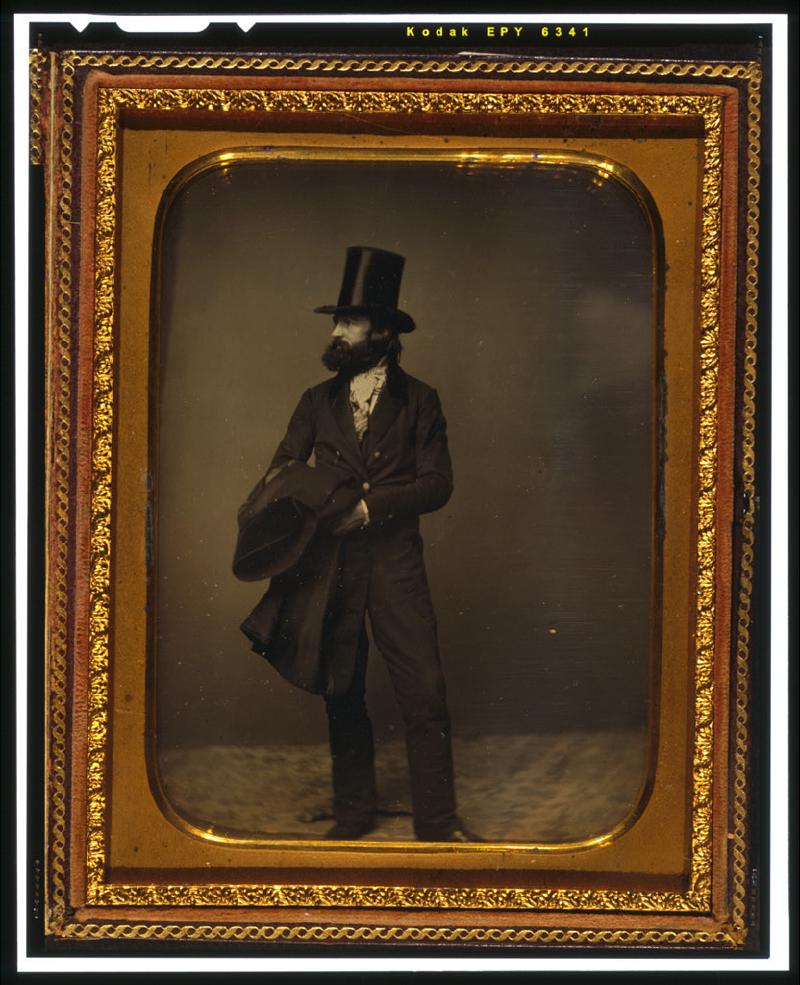

— William Sidney Mount, full length portrait, facing left, wearing top hat and holding a coat by Mathew Brady. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA, call number DAG no. 1279. View largest available size.

In the early years, some of Mount’s more prominent Long Island patrons were members of the Wells, Weeks, Mills, and Strong families.

— William Sidney Mount, Wikipedia.org.

William S. Mount ranks high among American artists and his work today is much sought after. Probably no one will ever be his equal in depicting the happy side of American country life. His “Power of Music” and “Farmer’s Nooning” are famous and in their engraved form have gone into many a home throughout our land. The scenes of most of his pictures are laid on Long Island, many of them near his home at Stony Brook. He lived during a considerable portion of his life in the Hawkins homestead at Stony Brook. He was in truth, Long Island’s artist—but his fame knew no bounds. Space forbids a longer account of his genius but the inquiring reader is referred to “Historical Miscellanies Relating to Long Island" by the compiler of this genealogy, where a more extended account of his life and work may be found. His brothers Henry S. and Shepard A, Mount were also artists of considerable ability. Shepard A. Mount’s portraits especially, take high rank.

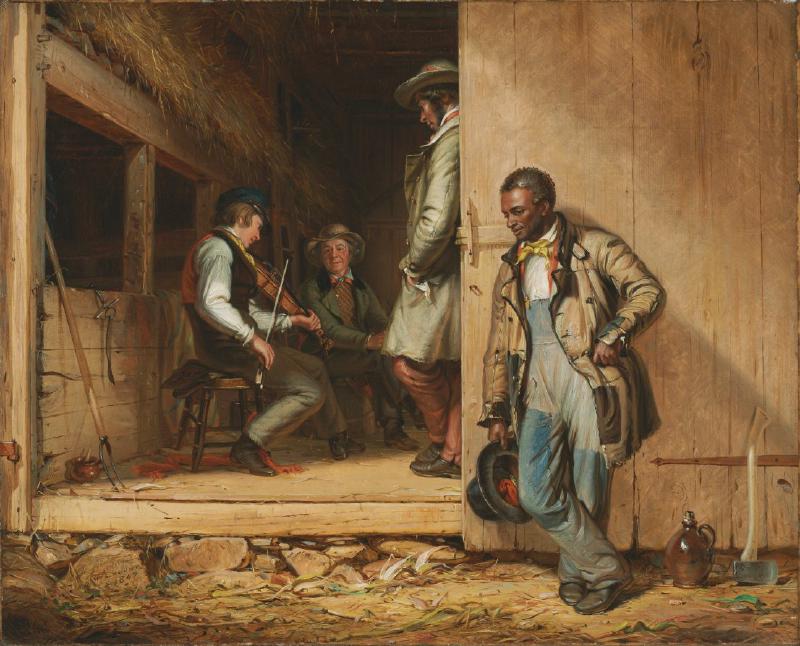

— 1836, Farmers Nooning by William Sidney Mount, Catalog Number 0000.001.1521, The Long Island Museum of American Art, History, & Carriages, Stony Brook NY. View largest available size.

— 1847, The Power of Music by William Sidney Mount, Accession No. 1991.110, Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland OH. View largest available size.

Mount’s fiddle performances for country dances convinced him there was a need for a violin that would project its sound loudly enough to be heard over the noise of the crowd. He also aimed to design a violin that had fewer parts than normal so that it could be manufactured more efficiently and affordably. Mount patented a hollow-backed violin, which he named the “Cradle of Harmony” in 1852. Mount experimented with various violin shapes and modifications for the rest of his life, with four different versions existing today. He displayed the instruments publicly and demonstrated one at the New York Crystal Palace Exposition in 1853.

— William Sidney Mount, Wikipedia.org.

— The Cradle of Harmony, Wikipedia.org, attributed to The Long Island Museum of American Art, History, & Carriages, Stony Brook NY. View largest available size.

The Riches of Sight: William Sidney Mount and His World

Material from the exhibition The Riches of Sight: William Sidney Mount and His World, July 27, 2002 - March 23, 2003, The Long Island Museum of American Art, History, & Carriages, www.longislandmuseum.org

The Riches of Sight: William Sidney Mount and His World opened July 27, 2002 in the Main Gallery of The Long Island Museum’s Art Museum. Drawn largely from the museum’s unsurpassed collection of paintings by William Sidney Mount (1808-1868), The Riches of Sight considers the many complexities of the life and work of this renowned American genre painter. For the exhibition, the main gallery of the Art Museum will be divided into three areas, allowing visitors to approach the works on display from any number of sequences and viewpoints.

One section sets forth the basic outline of Mount’s life, almost all of which was spent on Long Island and in New York City. Personal objects will enrich a large illustrated timeline setting forth the key events in the life of the artist and will relate them to national and international events of the period. An emphasis is placed on literary and artistic events that directly affected Mount, such as the publication of Thoreau’s Walden, which he read and admired, and the founding of the National Academy of Design, where he studied. An island in the center of the gallery will contain three artifact-rich vignettes featuring objects related to the artist, including paintings of the Hawkins-Mount homestead, furniture and other objects from it, and Mount’s personal collection of musical instruments and scores.

In another section, visitors explore influences on William Sidney Mount as a painter. Mount’s early paintings will be exhibited, in addition to his student sketches after prints by British artist William Hogarth and other European artists. For his entire life, Mount was aware of and affected by the work of these artists, as well as by the best-known American artists of the period, many of whom he counted as friends and colleagues. A stellar work in the exhibition will be John Vanderlyn’s Antiope, a dramatic painting of a lounging mythical woman after which Mount modeled the reclining black man in Farmers Nooning. Other, less traditional influences will also be included, such as phrenology, spiritualism, music, theater and politics.

The third section pairs contemporary criticism of William Sidney Mount’s paintings with the actual works being discussed by the critics – usually positively, but sometimes negatively. Replicas of reviews in The New-York Herald and The New-York Mirror, in addition to other newspapers and periodicals, will be displayed alongside the paintings. Why did this Stony Brook artist arouse such national and international interest? Visitors will be asked to consider what art criticism is and will be given a chance to submit their own reviews of Mount’s works. The exhibition will remain on view through March 23, 2003.

Also on view in The Art Museum is the Fine Lines: Drawings by William Sidney Mount exhibition. On view are twenty five line drawings produced by the artist over his forty year career. Many served as preliminaries to his paintings; others are simple musings. Themes represented are familiar ones to Mount’s paintings - theater life, politics, dancing, scenes of domesticity and marine life. This exhibition is the culmination of a six-month long preservation project sponsored by the archival supply company Nielsen & Bainbridge. The drawings will remain on view through September 6, 2002

Wall text from the exhibition The Riches of Sight: William Sidney Mount and His World:

Section I - Biography

Mount and Music

“I am confident that music adds to my health and happiness.”

Music strongly influenced William Sidney Mount’s life and art. When Mount was eight years old he was sent to live with an uncle, Micah Hawkins, who had a passion for the theater and music and passed this love on to his nephew, Hawkins was the composer of a successful operetta called The Saw-Mill, or A Yankee Trick and was known for entertaining customers with a piano he had built into a counter of the store he operated.

Mount was an accomplished violinist and was often invited to play the popular jigs, waltzes, and reels of the time at parties and dances. In 1852 he patented the “Cradle of Harmony,” a violin he designed to be more audible over the boisterous foot stomping typical of country dances. He displayed various models of the violin in 1853 at the Exhibition of Industry of All Nations in New York’s Crystal Palace.

Mount was very close to his brother Robert, a music and dance instructor. The only Mount son who did not make a career of painting, Robert traveled extensively most of his life, arranging performances and parties. William wrote his brother numerous letters in which he discussed fiddle playing and dancing. He would often include bars of music from songs he heard performed at area parties and even composed two of his own songs, In the Cars, on the Long Island Railroad and Musings of an Old Bachelor, both of which are seen in this exhibition.

William Sidney Mount’s musical inclinations and his talent for art intermingled in a complementary way. Many of the artist’s paintings make visible – sometimes seemingly almost audible – this blend of music and art. This fusion reaches a crescendo in Catching the Tune, where a probably autobiographical painting directs the viewer’s attention to the process.

Mount in the Country

“This is a very quiet place. Here one can retire from the busy world if he pleases.”

William Sidney Mount was born in Setauket, Long Island, and also died there, but the center of home life for him and his family was the Hawkins farm (now the Hawkins-Mount Homestead) in nearby Stony Brook, which had been in his mother’s family for generations. The property of ninety-some acres provided limitless sources of inspiration for his art: bucolic countryside, rustic outbuildings, a variety of farm animals, and hearty neighbors willing to pose.

Among Mount’s favorite subjects to portray were farmers and country gentlemen – to him the backbone of democracy. His family’s comfortable circumstances, and the early commercial success of his paintings, allowed him the freedom to paint when he liked and gave him an affectionate, and somewhat rose-colored, view of country life.

Mount participated in the life of his community, but his unmarried status probably prevented him from being fully integrated into it. His diaries are full of accounts of boating trips, attending socials and musical events, and participating in local spiritualist meetings. After his mother’s dearth in 1841, he inherited a partial ownership in the family homestead, along with his other siblings. But he never fully settled in there, moving in and out, often after disagreements with members of his extended family who also lived in the house.

Before William Sidney Mount, few American artists had looked to the lives of ordinary folk for inspiration, for only figures out of history, myth, literature, or the Bible were considered worthy of representation. Mount’s works depicting country people were enormously popular, and laid the foundation for a school of American genre painting whose effects are still felt.

Mount in the City

The nearness of New York City played an important role in William Sidney Mount’s development as an artist. He first became acquainted with the city when at the age of eight he was sent there by his mother to live there for a period with an uncle, Micah Hawkins, and his family. In his teens, Mount got his start as an apprentice to his older brother Henry, a sign and ornamental painter whose shop was located in Manhattan. And in 1826 be began his studies in the city at the newly founded National Academy of Design It was there that he came to know many of America’s most outstanding artists including Samuel F. B. Morse, Asher B. Durand, and Thomas Cole.

With the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825, New York City became the leading center of commerce in America, far surpassing its rivals, Philadelphia and Boston. This growth in affluence generated an ideal atmosphere for young artists as the new class of merchants and other entrepreneurs became interested in fine arts and culture. It was in this climate that Mount met prominent businessmen, such as Luman Reed and Jonathan Sturges, whose interest in art collecting and patronage helped launch his career.

William Sidney Mount’s feelings toward New York City were complex. Although he spent a great deal of time there, he never painted a single canvas with a specifically urban setting, even though he often observes, in his notes, the abundance of subject matter to be found there. He lived in New York for extended periods on several occasions, but, the dirt, the overcrowding and the general disorderliness of the urban setting soon impelled him back to Stony Brook. But there is no doubt that Mount understood the indispensability of the city to his career. He remained a member of the National Academy of Design, showed painting regularly in the city, and attended many of artistic and cultural events to which only the most eminent artists were invited.

Section II - Influences

William Sidney Mount, Participant in the Popular Trends and Enthusiasms of His Time

William Sidney Mount was deeply involved in the national and international issues that interested many educated and well-to-do mid-nineteenth-century Americans.

In the pre-Civil-War period, Mount was almost obsessed with national politics. Active in the Democratic party both in New York City and on Long Island, the artist carried on an impassioned correspondence on the leading political issues of the day, including those relating to electoral corruption, monetary speculation, Westward expansion, and the treatment of African Americans. All of these issues found their way into his paintings.

Other national movements and fashions of the day – among them phrenology and spiritualism – also influenced Mount’s life and his art. By no means the exclusive domain of the fanatic and the simple-minded, these “sciences” found disciples in many respected American political and cultural leaders of the period including James Fenimore Cooper, William Cullen Bryant, Horace Greeley – and even Abraham Lincoln. Mount was able, he reported, to contact not only deceased members of his family but also the great artists of the past.

Nor was Mount an entirely free spirit immune from the lure of the power of money and the people who had it. Many of his most famous works were painted as commissions ham wealthy New York merchants, publishers, and other entrepreneurs. Sometimes he was forced to redo paintings in order to please patrons. In appropriate cases he even included “product placements” in his works – for instance the well-labeled newspapers that appear in California News and The Herald in the Country.

Modem inventions and the general enthusiasm for “Improvements” fascinated Mount. He dabbled with inventions of his own, even patenting one – a reconfigured violin. The coming of train service to Long Island and its extension along the North Shore in the direction of Stony Brook was viewed as a great boon and a source far celebration, as in a fiddle tune Mount composed, “In the Cars, on the Long Island Rail Road.” Nature had its beauties, to be sure, but machines also had their attractions.

The Art Education of William Sidney Mount

William Sidney Mount was born into a family actively involved in the arts, with strong existing attachments to New York City. An uncle, Micah Hawkins, had had considerable success in Manhattan as a playwright and producer. William’s older brothers Henry and Shepard Mount went to New York at a young age to work as sign painters and portrait painters. And it was the amateur artwork of his sister Ruth that whetted Mount’s own interest in painting.

In 1826, at the age of eighteen, Mount enrolled in the recently established National Academy of Design in New York, where he worked alongside artists who had studied in Europe add was taught by instructors who had trained there. Mount’s schooling introduced him to European academic methods of art training and European art books, exposed him to European works of art, and allowed him to make the acquaintance of collectors whose galleries included European examples. In fact, he seriously considered traveling to Europe for study, but never did. And this, he said, was due to his fear that he might like it too much: “I might be induced by the splendor of European art too tarry too long, and thus lose my nationality.”

After his academic training, Mount continued to spend considerable amounts of time in New York City. While there he befriended other artists, actively participated in art organizations, received commissions from the city’s most eminent art patrons, and attended numerous exhibitions and theatrical and musical performances. Only in later years, after he had gained a national reputation and clientele, did he resolve to spend most of his time in the pastoral environs of Stony Brook – where the art world sought him out.

Even in his later years, William Sidney Mount carried on a voluminous correspondence with New York artists, critics, and patrons. He often visited New York – via steam packet or train – and friends and acquaintances from the city visited him. He continued to be involved at the National Academy and other art associations. And he maintained an impressive library, including works on art history and art theory, as well as other interests, some of which are included in this exhibition.

The Worldly William Sidney Mount

During his lifetime, the artist William Sidney Mount acquired the popular reputation of being a loner, a simple down~home sort who belittled European culture, disliked the cosmopolitan art world centered in New York City, and preferred to be among the ordinary folk of rural Long Island.

Belying this reputation, Mount enjoyed the finest classical art education then available in America, carefully studied European books and European art throughout his life, and counted as colleagues, friends, and patrons the most sophisticated artists and writers in the country. He was also influenced throughout his career by various new European art movements as they came into vogue in America.

Mount was also actively involved in mainstream popular concerns, from national politics to the widespread nineteenth-century fascination with what are now called ‘pseudosciences;" including spiritualism and phrenology. His interest in popular music is well known, and he worked at perfecting his skills at playing and writing tunes – and perfecting the designs of musical instruments – throughout his life.

All of this was directly reflected in the art of William Sidney Mount. The works in this gallery will reveal some of the ways in which the “outside” world molded and informed the work of this great American artist.

Section III - Critics

William Sidney Mount and His Critics

“An artist should remember that criticism does not alter the tone of a violin any more than the tone and merit of his paintings.”

Critical reviews seen in this exhibition are as they appeared in contemporary publications; many of the reviews have been copied from William Sidney Mount’s personal clippings and scrapbooks, An artist who was fully aware of his stature and position in the artistic world, Mount sometimes seemed to be obsessed with his reviews. He often commented in his journals and letters about his exhibits and their critical response. These clippings are an excellent research tool for future art historians and researchers, as they help to piece together an entire history of a painting, from the artist’s inception of the idea through its exhibition.

Art criticism in the United States has a very short history; before the nineteenth century art critics were virtually unknown creatures. Relatively little artwork was produced during the Colonial and Federal periods, and far less was publicly displayed. With the founding of the Pennsylvania Academy in 1805 and The National Academy of Design in 1826 American artists were afforded the opportunity for the first time to exhibit their work regularly in annual exhibitions. Critical reviews of these annuals began immediately and, with that, the field of American art criticism was born.

Many of the early reviews were printed in newspapers and periodicals, which were primarily literary or political in nature. Early critiques relied upon simple description, emphasized subject matter over anything else, and were simply lists of objects with brief descriptions or comments attached. Noticeable improvements in American criticism began to appear during the 1830’s and 1840’s, particularly with the increasing popularity of paintings by the Hudson River School painters, such as Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand. By the 1850’s new periodicals dedicated to art began to emerge. As American art increased in quantity and quality, critics increasingly made astute and precise observations and were able to move past puffery and hyperbole. Reviews in newspapers began to lengthen and were more detailed in content. By mid-century it was not uncommon for an exhibition review to be published serially, sometimes stretching over as many as eight issues. By the Civil War men and women began to find employment as “art critics” and it was around the same time that art reviews began to be more personal – and style, rather than subject matter or the personality of the artist, was emphasized.

y the end of the century art had become highly sophisticated. The last three decades of the nineteenth century saw the birth of the American art museum and the growth of commercial art galleries. American artists also became more aware of themselves as professionals and their patrons became more aware of art trends on both sides of the Atlantic.

Wall text from the exhibition Fine Lines: Drawings by William Sidney Mount:

Fine Lines: Drawings by William Sidney Mount

The Long Island Museum’s collection of artworks by William Sidney Mount (1807-1868) numbers more than 1,500 pieces. Mount’s artistic genius is most familiar to our visitors through his oil paintings – such as Farmers Nooning, Dance of the Haymakers, and The Banjo Player – of which we own more than 150. But, in actuality, the bulk. of the museum’s collection is made up of drawings (pencil or ink on paper) produced by the artist over the duration of his forty-year career.

Many of Mount’s drawings served as preliminary studies for his paintings. Others were produced simply as musings, random jottings, and exercises by an artist who found the act of drawing as natural and as necessary as breathing. Mount often followed familiar themes, such as home life, the seaside, theater, politics, and dancing, when he drew, and many of these scenes appear in his finished oil paintings.

This exhibition is the culmination of a six-month project sponsored by the archival supply company Nielsen & Bainbridge. Through a grant from its Partnership for Conservation program the company responded to the needs of the museum by donating the necessary acid-free archival materials to rehouse our Mount drawings. It is with gratitude to Nielsen & Bainbridge that we present these interesting works to out visitors.

Under the Canopy of Heaven: Works of William Sidney Mount

Material from the exhibition Under the Canopy of Heaven: Works of William Sidney Mount, September 11, 2009 - August 22, 2010, The Long Island Museum of American Art, History, and Carriages, www.longislandmuseum.org

William Sidney Mount came of age during one of the most exciting periods of American art. He was born in 1807 on Long Island in Setauket, but soon moved with his family to nearby Stony Brook. Mount was educated at the National Academy of Design in New York City, the most famous American art school of the early 19th century. He divided his time between New York City and the Stony Brook area, maintaining studios in both locations. In the city he took advantage of art and culture and met often with fellow artists, writers and musicians. But the countryside also exerted its pull, for Mount constantly returned to his rural roots, soaking up the atmosphere. Long Island’s characteristic landscape, with its verdant flora and engaging light, served him well in the backdrops of his most famous paintings.

Mount communicated frequently with New York’s Hudson River School" painters, early 19th century America’s dominant group of artists, who specialized in depicting nature as sublime and awe-inspiring. He was acquainted, in fact, with the leaders of this group – Thomas Cole, Asher B. Durand and John Frederick Kensett – and agreed enthusiastically with them as to the importance of elevating nature as a serious subject for painters.

However, there is a certain irony to Mount’s constant championing of painting outdoors, or en plein air. As the artist’s journals relate, although the background of every painting in this exhibition was indeed begun outside, from nature, each was in fact completed inside, in the artist’s studio. The central human figures, for instance, were almost always painted indoors, where it was more comfortable for both the artist and his subjects and where Mount could more easily control pose and lighting. The artist’s repeated extolling of the virtues of plein air painting, then, should be seen more as a reflection of then-prevalent fashion than as a literal description of his working methods.

By the time of Mount’s death in 1868, he had fallen under the influence of another preacher of the virtues of painting from nature. This was the English critic John Ruskin, who saw art, nature and morality as spiritually unified and advised artists to give exacting scrutiny to nature’s details in order to capture and portray its essence. To Ruskin, every detail was important: close attention must be paid to the precise details of each individual landform, the leaves on every tree, each blade of grass and the individual cornstalks growing in the late summer sun. Or, as William Sidney Mount put it, “Truth will speak – no second hand nature for me.”

Journal entries of William Sidney Mount within the exhibition

Pictures painted directly from nature will always captivate, will draw the spectator near. Truth will speak – no second hand nature for me.

I must use greater diligence in future and never distrust my own abilities. But paint every thing from nature, indoors and out morning noon and night.

– April 12, 1847

Painting from nature in the open air will learn the artist at once the beauty of the air tints from the horizon (sic) to the foreground. See how the dew sparkles on the foliage and the grass in the sun beams early in the morning.

How glorious it is to paint in the open fields, to hear the birds singing around you, to draw in the fresh air – how thankful it makes one.

— May 4, 1848

Work as much as possible from nature, indoors or out. Figures painted in the open air have a wonderful effect – providing the subject is good.

— March 19, 1854

A painters studio should be every where, wherever he finds a scene for a picture in doors or out.

— October, 1847

The foliage on Long Island remains greener much later than up the North river counties. Hence Long Island will be the last place in the autumn for artists to study landscape in the vicinity of New York City.

— October, 1847

My best pictures are those which I painted out of doors. I must follow my gift – to paint figures out of doors, as well as in doors, with out regard to paint room. The longer an artist leaves nature the more feeble he gets, he therefore should constantly imitate God An artist who has given himself up to nature should pay very little attention to critiques. The canopy of heaven is the most perfect paint room for an artist.

— December 29, 1848

I have been sketching landscape in oil good practice. If I should follow it up, I believe I would make a landscape painter. Nature, is the father and mother of art.

— October 7, 1858

Of Landscape:

White is the destruction of all glazing colours – the fore ground and its objects require all the strength and force of glazing which the colours are capable of producing

Landscape looks rich in the morning or evening. A view taken when the sun is just up, would look sparkling. Sittings could be taken every fair morning at the same hour, some remarkable scene or effect should be selected – The sun striking upon figures, or animals with their long shadows, etc.

— October 14, 1846

A Painter’s Studio is Everywhere: Paintings by William Sidney Mount

Material from the exhibition A Painter’s Studio is Everywhere: Paintings by William Sidney Mount, September 15, 2001 - June 16, 2002, The Long Island Museum of American Art, History, and Carriages, www.longislandmuseum.org

“A Painter’s Studio is Everywhere: Paintings by William Sidney Mount,” opened September 15, 2001 at The Long Island Museum. The exhibition, on view in the Member’s Gallery of the Art Museum, features eleven paintings by the renowned American genre painter William Sidney Mount, from the museum’s unparalleled collection of his works. The beauty of the exhibition extends beyond the art itself and lies in the insights provided by Mount’s personal written accounts of the paintings - their meanings and the inspiration behind them. Archival pieces on view, including Mount’s original diaries and letters, shed further light on the private thoughts of this publicly acclaimed figure. Despite the charming misspellings and grammatical errors, Mount’s written words on everything from politics to morality to artistic techniques paint a bold picture all their own.

Among the works on view are Farmers Nooning (1836), which brings to light Mount’s preoccupation with nature and sunlight. One of his diary entries in 1850 notes, “In painting a landscape - the shadows should be considered first; the more shadow, the more impressive the picture.”

Mount also kept a record of his social calendar, including visits by other painters. On one such visit in October of 1848, his friend, artist Charles Loring Elliot, painted Mount’s portrait. In his writings of it, Mount recounts “He has promised - sometime previous - that if I would sport a pair of moustaches, he would make me a present of my portrait. The hair and canvass was ready, and Elliot painted one of his best portraits. A man with a beard is nature in her glory.” Catch this natural wonder, on view, in A Painter’s Studio is Everywhere. (left: Charles Loring Elliot, William Sidney Mount, 1848)

Selected label text and wall text from the gallery exhibition

William Sidney Mount was born in Setauket, Long Island, and as a young boy moved, along with his brothers and sister, to nearby Stony Brook with his widowed mother, to live with her extended family. He studied painting in New York City at the National Academy of Design, the nation’s foremost art school, where his work was exhibited throughout his career. (left: William Sidney Mount, The Novice, 1847, oil on canvas, 0.1.4.992)

In his early years Mount primarily painted works with historical and literary themes. In 1829 the artist began to paint portraits and scenes from everyday life, or genre paintings. Mount’s scenes of rural life immediately became popular, both in the United States and abroad. By the middle of the nineteenth century he was one of the most renowned artists in America, with more commissions than he could fulfill.

While Mount had several opportunities to study abroad, he always declined, maintaining a strong nationalistic pride. He felt that such a trip might hamper his efforts to speak directly and simply to his fellow Americans through his genre paintings. Most of his famous works were created right here in Stony Brook.

Mount recorded everything. His diaries and correspondence filled with misspellings and grammatical errors include myriad opinions and observations on painting techniques, subjects for compositions, politics, music, morality, health, and the weather. These records greatly expand our insight into Mount’s art.

Each of the labels accompanying the paintings has been taken directly from the vast written material that Mount left behind. At times, Mount speaks very generally about his works, discussing technique, mood and composition. At other times he speaks very specifically about his art, as he does with his work The Novice. These specific observations are extremely helpful to art historians, as they are often the only glimpse into the artist’s mind during the creative process.

Do you like to paint or draw? Where is your favorite place to sit down and make a picture? William Sidney Mount, a painter from Stony Brook, thought that a painter should paint anywhere he liked. He even made a studio, or workshop, on wheels so that he could paint wherever he chose!

William Sidney Mount was born in Setauket, Long Island, on November 26, 1807. After his father died in 1814, he was sent to live with his uncle in New York City. At age seventeen, William went to work with to his older brother Henry, a sign painter, as an apprentice (someone who is learning a trade). Then he entered an art school called the National Academy of Design.

In 1829, William Sidney Mount came back to Long Island. He became famous for painting scenes of everyday life, called genre paintings. His paintings help us see what life was like over a hundred and fifty years ago.

Follow William Sidney Mount’s palette [ILLUSTRATE ONE HERE] through the exhibit to explore how and why Mr. Mount painted as he did.

Charles Loring Elliot (1812-1868), William Sidney Mount, 1848, Oil on canvas, Gift of Edith Douglass, Mary Rackcliffe and Andrew E. Douglass in memory of Mrs. Moses Douglass and Mrs. Scott Kidder, 1956

The last of Oct. 1848, Mr. Elliot made a visit at Stony Brook. He had promised sometime previous that if I would sport a pair of moustaches, he would make me a present of my portrait. The hair and canvass was ready, and Elliot painted one of his best portraits. A man with a beard is nature in her glory.

— Diary entry, January 1854

William Sidney Mount’s artist friend, Charles Loring Elliot, said he would paint his portrait, or a picture of him, if he agreed to grow whiskers. Mr. Mount did just that! How do we get pictures of our friends and family today?

Benjamin Franklin Thompson, 1834, Oil on canvas, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Ward Melville, 1975

I had a visit to day from Benj. Franklin Thompson. He had a great deal to say about the Monument to Gen. Nathaniel Woodhull he is one of the committee to carry it into execution. It is a noble undertaking and when finished will do honor to Long Island and those concerned in it.

— Diary entry, December 12, 1848

William Sidney Mount also painted pictures of people, called portraits. Compare this painting to the painting of Mr. Mount’s sister, Ruth.

The Novice, 1847, Oil on canvas, Museum Purchase, 1962

I am pleased that you like my picture of the Novice, and speak so free of it. . . . In many respects, I think it is my best picture. . . . Mr. Patterson, a friend of mine and a love of painting, says that it is the most brilliant in colour that I have painted. .. . In the Novice I wished to preserve breadth and to tell my story. If figures are principal, everything else should be subordinate depending on the taste of the artist. When landscape is primo, and figures are introduced, they are and must be secondo.

— Letter to Charles Lanman, September 9, 1847

William Sidney Mount liked to paint people enjoying music. He played the violin and even wrote a song. A novice is a beginner. Who is the novice in this painting?

Portrait of Ruth Mount Seabury, 1831, Oil on canvas, Gift of Mary Rackcliffe and Edith Douglass, 1970

My sister, Ruth H. Seabury, although the youngest, displayed the first taste in painting when at the early age of eleven she took lessons of Mrs. Spinola. Then you could have seen me looking over my sister’s shoulder, with my straw hat in hand, to see how she put on the colours. A picture was then and always has been to me an object of great attraction.

— Autobiographical sketch, undated

William Sidney Mount said he first got interested in painting after watching his sister, Ruth, paint when they were children. Look to see how Mr. Mount used many simple shapes, like circles, triangles and squares to make his sister’s picture. How many different shapes can you find?

Farmers Nooning, 1836, Oil on canvas, Gift of Frederick Sturges, 1954

As long ago as 1836 when I was painting The Farmers nooning my late brother H. S. Mount, handed me a piece of native umber found in the banks near this place and desired me to make use of it in my picture I did so and found it as he had represented, transparent, and a good dryer I have used it more or less ever since and find it a valuable pigment In the gradations of flesh, with white it is truly delightful.

— Letter to Benjamin Thompson, December 31, 1848

William Sidney Mount used colors and shadows to make his paintings look more real. Can you find the shadows in this painting? Count all the different colors Mr. Mount used to just paint the trees and sky. Look at the other paintings and see if you can find any of the same colors.

Right and Left, 1850, Oil on canvas, Museum Purchase, 1956

I believe I must have a violin in my studio to practice upon. To stimulate me more to painting. I remember that when I painted my best pictures I played upon the violin much more than I do now. The violin was the favorite instrument of Wilkie. All the great painters were fond of music.

— Diary entry, February 16, 1863

William Sidney Mount knew the musician who sat for this portrait. Count how many people are playing or enjoying music in all of Mr. Mount’s paintings.

Dancing on the Barn Floor, 1831, Oil on canvas, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Ward Melville, 1955

In finishing a painting be careful and give force to the foreground darks and lights. Strengthening the foreground tones down the distance.

— Diary entry, April 1, 1851

William Sidney Mount’s paintings also showed people at play. The man playing the violin is in the front, or foreground. The dancing man and woman are in the middle ground. The woman with the broom is in the background. How does Mr. Mount use different sizes and colors to make things look further away or closer up?

Catching Rabbits, 1839, Oil on panel, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Ward Melville, 1958

Boys Trapping painted for Chas. A. Davis of N.Y. in 1839 it is now in Paris under the magic hand of Leon Noel, and then both of the . . . pictures [this one and Just in Tune], after serving the purposes of the engraver, are to be exhibited in the ensuing collection of paintings at the Tuilleries.

— Letter to Charles Lanman, January 7, 1850

Compare this painting to Catching Crabs. How are the paintings alike? How are they different? Which person would you like to be in either of these paintings?

Catching Crabs, 1865, Oil on canvas, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Ward Melville, 1958

I must paint such pictures as speak at once to the spectator, scenes that are most popular that will be understood on the instant.

— Diary entry, July 1, 1850

William Sidney Mount lived most of his life on Long Island and he painted many Long Island landscapes or outdoor scenes. What are some of the different farm jobs Mr. Mount showed in this painting? Does he make farm life look easy or hard? How does he give you that feeling?

The Sportsman’s Last Visit, 1835, Oil on canvas, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Ward Melville, 1958

…painted in Setauket in 1835 at the house of Gen. Satterlee by the aid of two south windows in winter and separated by a curtain to divide the two lights. The artist by one window & the model by the other. . . .

— Diary entry, November 14, 1852

William Sidney Mount liked to use natural light in his paintings. Which character does the light shine on in this painting? In what other ways are your eyes drawn to this person?

Mischievous Drop, 1857, Oil on canvas, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Ward Melville, 1955

Strive more to paint from memory the scenes you witness. To sketch or paint them daily as they occur.

— Diary entry, 1857

Many of William Sidney Mount’s paintings tell stories. What do you think might happen next?

Is Art Hereditary? The Mounts, A Family of Painters

Material from the exhibition Is Art Hereditary? The Mounts, A Family of Painters, June 23 through September 9, 2001, The Long Island Museum of American Art, History, and Carriages, www.longislandmuseum.org

William Sidney Mount, termed America’s finest genre painter, is an acclaimed artist who achieved international recognition. What may not be so widely known is that Mount comes from a family of painters, each important to the art scene in their own right. The Is Art Hereditary? The Mounts, A Family of Painters exhibition examines the work of other, lesser known Mount family members. In the gallery will be impressive works from Mount’s brothers, sister, and niece.

It was actually William’s eldest brother, Henry Smith Mount (1802-1841) who provided his younger brothers with their first glance into the New York art scene. Henry painted primarily still lifes. Among his works on display during this exhibition are Girls and Pigs (1831) and Fish (1831).

Next in the Mount family of painters is Shepard Alonzo Mount (1804-1868). The springboard for his art training was initially in the painting of carriages. This honed his vision for a unified style, application of color theory and the harmonious placement of color. He went on to study at the National Academy of Design and to achieve success as a portrait painter. Some of his portraits on display include Rose of Sharon (Remember Me) (1863), and Portrait of William Sidney Mount.

The youngest Mount sibling, Ruth Hawkins Mount (1808-1888) was, ironically, the first to express an interest in painting. She studied formally and worked primarily in watercolors. Her collection reflects traditional 19th century women’s art. Her L’Orage (The Storm) (1820-1826) watercolor on paper is part of the exhibit.

The painting tradition lived on in the next generation of Mounts, when Evelina (1837-1920), daughter of Henry Smith Mount, gravitated to a life as artist. Raised in Stony Brook, her family home served as subject for most of her paintings. Her floral paintings are deemed her most original in concept. Catching Butterflies (1867) is among her works on view.

The most acclaimed of the Mount family of painters, William Sidney Mount (1807-1868), is also represented in the exhibition. Famed mainly for his scenes from “ordinary life,” he also attained significant success as a landscape painter and portraitist. Featured in this exhibit are Dance of the Haymakers (1845) and Shepard Alonzo Mount (1847).

Following is wall text from the exhibition:

The oldest of four artistic brothers, Henry Smith Mount (1802-1841), was primarily a painter of still lifes. As a young man, he studied sign and ornamental painting and by 1824 had his own sign-painting business in New York City. It was Henry who gave his brothers Shepard and William their first exposure to the New York art scene. Henry’s election as an associate of the National Academy of Design in 1828 gave him the opportunity to advance his talents, and his two artist brothers would follow him.

Shepard Alonzo Mount (1804-1868) was initially trained in the art of painting carriages, which enabled him to sharpen his eye for concerns of unified style, application of color theory, and the arrangement of harmonious colors. Later he studied at the National Academy of Design and went on to become a successful and well known portrait painter.

Robert Nelson Mount (1806-1883) exercised his artistic talents in another way–through music. He was a traveling musician and dance teacher in the American South for most of his life but kept in close touch with his Long Island family through frequent correspondence and occasional visits.

The career of William Sidney Mount (1807-1868) was one of the great success stories of the nineteenth-century American art world. Also a product of the National Academy of Design, by his early thirties he was praised by a New York critic as “one of the most gifted artists that ever lived.” For most of the rest of his life, he had patrons waiting in line to buy works from him. He is best known for his paintings of genre subjects, scenes from “ordinary life.” He was also an accomplished portraitist and landscape painter, and his works were reproduced and distributed throughout Europe and the United States.

The only Mount sister, Ruth Hawkins Mount (1808-1888), was the youngest child but the first to express an interest in painting. William recounts in his autobiography that she was an influence on him, rather than vice versa: “at the early age of eleven she took lessons of Mrs. Spinola. Then you could have seen me looking over my sister’s shoulder with my straw hat in hand, to see how she put on the colours. A picture was then, and always has been a great object of attraction.”

Evelina Mount (1837-1920): daughter of Henry, was a member of the following generation. “Nina” was raised in Stony Brook in the Hawkins-Mount family homestead. She was undoubtedly influenced by the art of her uncles William and Shepard and, as they did, used the family home as a frequent subject for her paintings. She probably did not consider herself a professional, and rarely sold work. The most original in concept are her floral paintings.

Background and caption information for the exhibition:

(left: Ruth Hawkins Mount (1808-1888), L ‘Orage (The Storm), 1820-26, Watercolor on paper, Gift of Mary Rackliffe and Edith Douglass, 1970)

The only daughter of Julia Ann Hawkins and Thomas Shepard Mount, Ruth was the first member of the Mount family to take an interest in painting. William recounts in his autobiography, “at the early age of eleven she took lessons of Mrs. Spinola. Then you could have seen me looking over my sister’s shoulder, with my straw hat in hand, to see how she put on the colours. A picture was then, and always has been an object of great attraction.” Ruth later married Charles Saltonstall Seabury, a local piano maker.

(left: Henry Smith Mount (1802-1841), Girl and Pigs, c. 1831, Oil on panel, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Ward Melville, 1976)

William Sidney Mount included this painting of pigs by his brother Henry in his composition for California News. It has been suggested, that this is the artist’s silent comment on the greed of those who hunger for gold.

The oldest of the Mount brothers, Henry Smith Mount was primarily a painter of still lifes. As a young man, he studied sign and ornamental painting with Lewis Child, and by 1824 he had his own sign business on Chatham Street in New York City. It was Henry who gave his brothers Shepard and William their first exposure to the New York art scene. Henry’s election as an associate of the National Academy of Design in 1828 gave him the opportunity to advance his talents from sign painting to still-life painting. From 1828 until his death, he exhibited a total of eighteen paintings at the National Academy annuals.

(left: Shepard Alonzo Mount (1804-1868), Rose of Sharon (Remember Me), 1863, Oil on canvas, Gift of the Estate of Dorothy deBevoise Mount, 1959)

In 1861, Shepard Mount’s daughter Ruth (“Tutie”) died from tuberculosis. The family’s sorrow at her untimely death at the age of nineteen was compounded by the fact that she had just been married. Tutie was her father’s favorite model, and she appeared in many of his “fancy pictures” where she epitomized the ideal female. In addition to the loss of his daughter, Shepard was further grief-stricken in 1863 when he learned that his eldest son, William Shepard Mount, had been arrested and imprisoned as a spy during the Civil War. This situation coupled with Tutie’s death may have prompted him to paint Rose of Sharon (Remember Me).

The flowers in the work have been interpreted as an allegory of the human life cycle. The largest rose of Sharon flower in the vase is Shepard Mount himself. Shielded behind it are two buds meant to signify the artist’s two younger sons, Joshua and Robert. The separated red flower in the vase symbolizes William Shepard Mount and his uncertain fate. Finally, Mount depicts the deceased Tutie in the form of the ripped bud lying on the ground. Tutie’s soul is represented above the vase of flowers in the form of a shooting star rising towards the heavens.

(left: Shepard Alonzo Mount (1804-1868), Portrait of Camille Mount, 1868, Oil on canvas, Gift of the Estate of Dorothy deBevoise Mount, 1959)

Camille, daughter of Joshua Elliot Mount and Edna Searing Mount and granddaughter of Shepard, died before her second birthday. In a letter to his son William, Shepard writes,

Telling you of Joshua and Edna . . . they have lost their little Camille - she is dead - the sweet beautiful babe is dead. She died from the effects of teething. It so happened - Providentely [sic] I thought - that I was in Glen Cove - and for two or three days before she died I made several drawings of her which enabled me, as soon as She was buried to commence a portrait of her and in 7 days I succeeded in finishing one of the best portraits of a child that I have ever painted.

Painting posthumous portraits was a common nineteenth-century mourning ritual. William Sidney Mount, for instance, received many commissions for mourning portraits, several of which are in our own art collection.

(left: William Sidney Mount (1807-1868), Portrait of Shepard Alonzo Mount, 1847, Oil on canvas, Museum Purchase, 1960; right: Shepard Alonzo Mount (1804-1868), Portrait of William Sidney Mount, 1857, Oil on panel, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Ward Melville, 1976)

Throughout their lives, Shepard and William Mount maintained a close working and personal relationship, attending functions at the National Academy together, acting as business partners, and sometimes living with each other. When Shepard died in 1868, William was distraught and immediately arranged for a retrospective exhibition to be hung at the National Academy of Design. The following fall, William was stricken with pneumonia and died, only four months after his older brother.

From Cradle to Grave: The Works of William Sidney Mount

Material from the exhibition From Cradle to Grave: The Works of William Sidney Mount, January 13 - June 17, 2001, The Long Island Museum of American Art, History, and Carriages, www.longislandmuseum.org

A new exhibition exploring the depiction of the human life cycle in the paintings of American genre painter William Sidney Mount opens January 13, 2001 at the Long Island Museum of American Art, History & Carriages. From Cradle to Grave: The Works of William Sidney Mount features 15 original works by the renowned artist. Organized by The Long Island Museum and drawn from its collection, the exhibition will be on view through June 17, 2001 in the Members Gallery of the Art Museum. (left: School Boys Quarreling, 1830, oil on canvas, Museum purchase)

Nineteenth-century Americans had distinct ideas of how each stage of life should be rendered. The classical depictions in the prints The Life & Age of Man and The Life & Age of Woman, published by James Baillie in 1848, are used in the exhibition as a springboard for discussion of the 19th-century perception of aging as recorded and interpreted by Mount. (right: The Sportsman’s Last Visit, 1835, oil on canvas, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Ward Melville, 1958)

The exhibition begins with the portrayal of childhood in Mount’s works School Boys Quarreling (1830) and Mischievous Drop (1857). The rituals of adolescence and young adulthood are also included, as in The Sportsman’s Last Visit (1835) where courtship is the focal subject. (left: Girl Asleep (Maria Seabury), 1843, oil on canvas mounted on panel, Museum purchase, 1956)

“Middle age” was held to be the most productive period of 19th-century life. Frequently Mount used local residents as subjects for his works, depicting the gentleman farmer working or discussing politics, for example. Long Island Farmer Husking Corn (1834) and Herald in the Country (1853) are two wonderful portrayals of the prosperity, energy and intellect of the 19th-century adult figure.

Mount used elderly models as subjects for many of his works. The rather gaunt portrait of his mother, Julia Ann Hawkins Mount (1830), is a good example. Painted when Mrs. Mount was only 43, she had by that time endured eight pregnancies - five children lived past infancy - and had been a widow for over 15 years. In this work, her son sensitively captures the effect on her of this difficult life.

Finally, Mount’s interest in spiritualism, combined with 19th-century mourning rites, led to his production of posthumous paintings. Among the best known are his portraits of Jedidiah Williamson (1837) and Susie T. Marsh (1860), who both died in childhood. Although Mount realized that commissioning a death portrait of a child was part of the mourning and grieving process for families who could afford it, he disliked this type of work and was known to charge more than double his regular fee for such paintings.

William Sidney Mount: Music Is Contagious!

Material from the exhibition William Sidney Mount: Music Is Contagious!, January 15 - June 18, 2000, The Long Island Museum of American Art, History, and Carriages, www.longislandmuseum.org

A selection of works by acclaimed genre artist William Sidney Mount that testify to his lifelong love of music will be presented at The Museums at Stony Brook from January 15 through June 18, 2000. A talented musician as well as a respected artist, Mount played a variety of instruments, including the fiddle, piccolo, wooden flute, recorder, and fife. His writings reveal that he was a serious instrumentalist, composer, and collector of music as well. He was also an inventor: in 1852 he patented a unique design for a hollow-back violin that he called “The Cradle of Harmony.” By the time Mount died, he had collected over 500 pieces of manuscript music and composed original compositions. (left: Dance of the Haymakers, 1845, oil on canvas, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Ward Melville, 1950, The Museums at Stony Brook)

During Mount’s lifetime (1804-1868), interest in new forms of musical expression grew, and the advent of singing schools, classes in instrumental music, community concerts, and Fourth of July celebrations drew widespread participation in musical activities. Less formal pastimes, such as fiddling in the parlor after dinner, neighborhood dances and impromptu gatherings in local barns, all provided opportunities for the simple musical enjoyment that was captured in many of Mount’s works. (right: The Banjo Player, 1856, oil on canvas, 35 3/4 x 28 3/4 inches, The Museums at Stony Brook)

“The Music Is Contagious!” exhibition includes works of art, musical instruments, and memorabilia relating to William Sidney Mount and his family.

William Sidney Mount: Painter of American Life

Material from the exhibition William Sidney Mount: Painter of American Life, June 12 - September 26, 1999, The Long Island Museum of American Art, History, and Carriages, www.longislandmuseum.org

Following a national tour, the exclusive William Sidney Mount: Painter of American Life will open in The Museums at Stony Brook’s Art Museum on June 12, 1999, where it will remain on view through September 26, 1999. For the past nine months, The Museums’ collection has been shown at The New-York Historical Society, The Frick Museum of Art (Pittsburgh, PA) and The Amon Carter Museum (Forth Worth, TX) .

“Mount is among the greatest, most innovative painters in our nation’s history, but because the majority of his work is in Stony Brook, few people outside our region were even aware of his achievements,” states Deborah J. Johnson, Museums’ President and CEO and Curator of the exhibition. “The travelling exhibition and the accompanying publication have brought Mount’s paintings to national attention.” The exhibition has also received notable feature coverage in The New York Times, The Magazine Antiques, CNN and Time magazine. Resource Library’s 1998 article on William Sidney Mount: Painter of American Life at the New-York Historical Society is also available for your viewing.

In addition to featuring The Museums’ William Sidney Mount masterpieces that traveled, Johnson will expand the scope of the show to include other pieces drawn from The Museums’ collection. “We have a national treasure in the Mount Collection,” says Johnson. “To fully appreciate the importance of the artist’s achievements, I encourage everyone to see this summer’s exhibition.” Featuring 75 original paintings, drawings, prints and sketches, the exhibition reveals how thoroughly William Sidney Mount’s images illustrate 19th century American society and culture.

A Long Island native, Mount (1807-1868) is widely credited as the originator of American genre painting.

At a time when other American artists adhered to European models, Mount successfully transferred these traditions into imagery specific to American life. He was the first in this country to focus on scenes of everyday life. Many of his paintings also include vividly realistic images of his friends and neighbors from Setauket and Stony Brook. His personal belief regarding his work, “Never paint for the few but for the many,” gave average Americans the chance to view themselves, for the first time, as subjects of art. His paintings struck a sympathetic chord with both the public and critics, who pronounced the artist one of the most talented of his time.

The exhibition is accompanied by a book of the same name, William Sidney Mount: Painter of American Life, published by the American Federation of Arts and available at The Museums’ Gift and Book Shop. Johnson authored the main essay for the publication and states, “The book will stand as the definitive study of the artist’s life and career for many years to come.” Other contributors include Elizabeth Johns, Professor of American Art History at the University of Pennsylvania; Franklin Kelly, Curator of British and American Paintings at the National Gallery of Art (Washington D.C.); and Bernard F. Reilly, Jr. Director of Research and Access at the Chicago Historical Society. The Henry Luce Foundation (NYC) has provided funding for the publication.

The Roslyn Savings Foundation has provided major funding for the local venue of William Sidney Mount: Painter of American Life.